In 1996, cheered on by an up-and-coming national energy company named Enron, the California Legislature passed AB 1890, a bill to phase in electric deregulation. It was a disaster of historic proportions.

For decades, regulated monopolies like PG&E had made steady money providing reliable service. Now other companies were angling for a piece of the action. But these unregulated power companies didn’t have the legal obligation, the financial incentives, nor the moral disposition to think about deregulation’s impact on service and the workers who provided it.

In fact, Enron regarded workers as a liability. “Depopulate. Get rid of people. They gum up the works,” Enron President Jeffrey Skilling advised fellow executives in 1997.

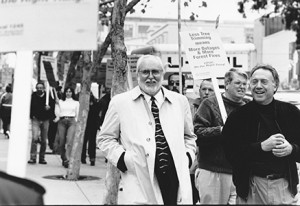

Business Manager Jack McNally, left, and IBEW Legislative Advocate Art Carter picket in 1999, urging the CPUC to protect service reliability. IBEW 1245 Archive photo by David Bacon

In May of 1997 the CPUC ruled that firms like Enron could perform metering, billing, collections and customer service functions traditionally handled by PG&E. By 1999 there was serious talk about forcing PG&E out of hydro-electric generation and opening up electric distribution to companies like Enron.

But Enron, it turned out, was a criminal enterprise. With Enron leading the way, unregulated power producers and traders jacked up wholesale prices to exorbitant levels. They joked in vulgar emails about all the money they were stealing from “Grandma Millie.” They concocted schemes with names like “Black Widow” and “Death Star” that intentionally deprived the state of electric power and forced it to institute rolling blackouts. When California’s total electric bill, just $8 billion in 1999, was on track to hit $70 billion in 2001, shell-shocked legislators coughed up $45 billion in taxpayer dollars to purchase long-term power contracts, which finally staunched the bleeding.

More than two dozen Enron executives, including President Skilling, were ultimately convicted of crimes. About two dozen other energy-related companies were penalized in connection with California’s manipulated energy markets.

The deregulation fiasco drove PG&E into bankruptcy, but a coalition of utility unions headed by IBEW 1245 successfully petitioned the CPUC to block layoffs. This confirmed McNally’s belief that the union needed a big presence in the political arena to protect its members.

But IBEW 1245 members, buffeted by years of instability in the utility industry, were ready for a change. In 2001 they elected former Assistant Business Manager Perry Zimmerman to replace McNally.