Webmaster’s note: This extended chapter on Sierra Pacific Power is taken from Fist Full of Lightning, the history of IBEW 1245.

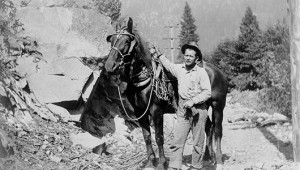

Horses and mules were indispensable to early linemen working in the Sierras. This lineman probably worked for Great Western Power. IBEW 1245 Archive

Utility workers in Nevada and California belonged together. Utility workers on both sides of the Sierras had fought together for the eight-hour day in the early 1900s and Business Manager Ron Weakley knew they still needed each other a half-century later. They had much in common. They faced the same hazards and in many cases they labored in the same mountainous terrain. They packed in supplies with mules, dragged poles with horse teams and wagons, forded rivers by raft, and set poles by hand. In 1923 linemen built a 60,000-volt line across the Sierras that physically connected the infant electric grids of the two states and joined the fates of their utility workers. From the moment the IBEW chartered Local 1245 in 1941 to organize PG&E it was well understood that Northern Nevada linemen had to be part of the equation.

One of the earliest and most ardent IBEW supporters in Nevada was Gas Meterman George Kaiser. A Kansas native, Kaiser had been hired by Sierra Pacific Power in 1934. He was already 41, an experienced worker, and his enthusiasm helped bring the union spirit out of its long hibernation at the Nevada utility. In February of 1944, IBEW 1245 petitioned the National Labor Relations Board for a union election.

SPP dug in its heels. The utility claimed its employees were already represented by the Sierra Utility Workers’ Union, a company union established in 1938. But the NLRB ruled that an election was appropriate because a “substantial number” of employees, thanks to organizers like Kaiser, already belonged to the IBEW. Next, the company pressed to have Clerical employees included in the election, hoping it might dilute the pro-union vote. The NLRB ruled that Clerical employees would vote, but as a separate bargaining unit. In the end, it didn’t really matter. On June 8, 1945, both groups voted overwhelming for the IBEW: Physical 76-11; Clerical 27-10.

It was slow going at first. SPP didn’t sign a labor agreement until 1947. But in the aftermath of World War II, the company was attracting a new generation of young workers who would steadily strengthen the union’s hand.

One of them was Sylvester Kelley, who applied for a job with SPP right out of the army in 1946. The company wouldn’t take him because one of Kelley’s fingers had been mangled by German shrapnel during the war and wouldn’t fit inside a work glove. Undeterred, Kelley went to a doctor, had the finger amputated and then re-applied. SPP put him to work digging ditches in Lovelock, NV. When another employee suggested he ought to join the union, Kelley simply asked where to sign. “I wasn’t going to be one of those that says ‘no,’” Kelley recalled more than 60 years later.

After the company transferred Kelley to Carson City, a foreman got in the habit of keeping the men an extra 15 minutes after work each day—without pay. The men put up with it for a while, but then filed a grievance. Kelley recalled the supervisor’s reaction with a mischievous grin: “He got mad, man.” Sometimes the boss would insist that the men work in the rain and the snow, even when there was no emergency. “If it’s an emergency it’s a different story,” Kelly allowed. “But if it’s pouring down rain—you’re getting wet, you’re working high voltage, it’s dangerous.”

When a co-worker went on vacation over Christmas, Kelley remembered the foreman complaining: “I don’t know why Glen don’t come back to work. I’m sure the company would pay him if he’d come back to work. We need him.” He didn’t get any sympathy from Kelley, who replied: “Don’t you ever call me when I’m on vacation because I won’t come in.”

IBEW 1245 had no union meeting in Carson, so Kelley began attending the one in Reno. By the mid-1950s he was serving as the Reno unit chair, a position he held for about a decade. In 1960 he hosted a meeting at his house with Ron Weakley and other union members trying to drum up support for John F. Kennedy, who was running for U.S. President against the shameless red-baiter Richard M. Nixon.

Sierra Pacific Power Co. personnel in Reno, Nevada in the late 1950s. Orv Owen is the tall guy right-of-center, in back. IBEW 1245 Archive

Another of the early union activists at SPP was a powerfully-built young worker named Orville Owen. Owen began work in 1949, assigned to a gas crew. In that era, he later recalled, the work was strictly hands-on. You had a pick, a shovel, a jackhammer—and whatever strength you could bring to the job. It didn’t take long for Owen to come to management’s attention. One day while working on a gas job, Owen was using a gargantuan 125-pound Gardner Denver jack hammer to cut through the blacktop. Many workers shied away from that model because of its size, but Owen, who stood several inches over six feet, liked it for its balance. The utility’s vice president, Fairchild Barnett, happened to drive by and noticed Owen outrigging the giant jackhammer with his leg.

“He stopped, he backed up and he waves to me and says, ‘Hey, young fella. I’m gonna get one for your other leg.’ And I says, ‘That’s all right, but you’re gonna pay me twice.’”

It was Owen’s first negotiation with SPP management but it wouldn’t be his last. With encouragement from George Kaiser, Owen got involved in the union. Local 1245 Business Representative Al Kaznowski soon appointed Owen to the grievance committee and then to the negotiating committee. That’s where Owen met Ron Weakley and L. L. Mitchell. Mitchell remembered Owen as a determined negotiator, not easy to move off a position.

“He did have a temper. If things went too awry, he expressed himself, maybe threatening to throw a fellow out the window,” Mitchell said.

“It was only the second floor,” Owen deadpanned when giving his version of the story.

In those days, the union often negotiated directly with Frank Tracy, the head of SPP. The union had one distinct advantage in these negotiations: the comptroller of the company, Al Peterson, was a bargaining unit member and served on the union’s negotiating team. Mitchell recalled:

“Anytime the president of the company said we don’t have enough money to give you this or that, the comptroller would say, ‘Look here, Tracy, we do too.’”

The union had its work cut out for it in those early negotiations. “We didn’t have anything,” recalled Bill Campbell, a line foreman who went to work for SPP in 1951 and retired in 1990. “You never heard of a rest period. We worked 40 hours at a shot. We just laid down on the cement floor of the warehouse and then we’re off again.”

Peter Vanni, a lineman who went to work for SPP in 1948, remembered what it was like trying to keep the Tahoe area powered up in winter. “Getting around in the snow, we used to have to snow shoe or ski—there just wasn’t any other way. No snowcats or anything like that. But the circuits around the lake had to be kept open. So you’d pick up your wire, jacks and ropes and you’d go do it.”

Campbell remembered working on a line during a particularly nasty winter storm:

The wind was coming at 80 miles per hour. You could hear trees busting off and everything. I remember one tree busted about two spans away and rattled everything when it came down. It must have been about midnight. This one kid came off that pole and quit. He said, “I ain’t staying up that damn mountain.”

But Campbell stayed because, well, that’s just what linemen did. “You never came off that mountain until that job was done,” he said.

Given how dangerous the work could be, it was no wonder that Nevada linemen wanted more control over their working conditions. Even wrangling a meal could be a challenge. “You’d eat when they wanted you to eat,” said Vanni.

Nevada was (and remains) a right-to-work state, where unions are barred from negotiating union security clauses in their labor agreements. This opened the door for free riders, and made it necessary for IBEW 1245 to sign up each member individually.

“When I first started (in 1949) there was about 52% union membership at the power company,” said Tom Lewis, who would go on to serve as shop steward, unit chair, and negotiating committee member. “The company was growing and the time was ripe for people to get into the union. I loved it.” Lewis had come from the textile mills of the East, where there’d been no union to protect him. At SPP, he immediately began recruiting for the union. Others were doing the same thing. Membership grew. A substantial majority of workers in the 1950s not only joined but also signed up for dues checkoff, meaning their dues could be automatically deducted from their paychecks and transferred to the union.

Ron Weakley and L. L. Mitchell often participated personally in the Nevada negotiations. In 1953 and 1954 the union negotiated improvements in vacation and sick leave, laid the foundation for apprentice training programs and began pushing for greater contributions by the company to the health and pension plans. As at PG&E, the union was laying a foundation of wages and benefits—something that could be built on during each subsequent round of negotiations. IBEW 1245 had forced the company to take into account the hopes and aspirations of its employees. But bosses still found ways to make things difficult.

In 1960, when the union needed to raise dues, management insisted that all of the dues checkoff cards were now invalid and that employees had to sign up all over again. The company may have hoped that employees would be upset by the inconvenience and drop out of the union, but that’s not what happened. According to Owen, union stewards took stacks of new cards and in just three weeks signed up 85% of the entire workforce, including everyone who had belonged before plus eight new members.

“We had a real tight group up there,” Owen said.