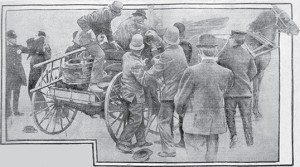

Three IBEW 151 linemen in their PT&T line wagon are chased by police after they blocked the

tracks during the 1907 street car strike. Call/SFHC/SFPL/SB 18

On May 8, 1907, San Francisco police were ordered to keep the street cars running—basically, to serve as strikebreakers. The striking carmen had to prevent that from happening, or else give up their fight for the eight-hour day.

Mid-afternoon, two street cars headed out from the car barns, with a heavy escort of police. Vast crowds followed behind on foot. After the previous day’s carnage, no one tried to stop the street cars. But at the intersection of Hayes and Masonic, three PT&T linemen pulled their horse-drawn repair wagon onto the tracks. IBEW 151 hadn’t officially joined the strike yet, but these linemen believed it was a matter of honor to help the street carmen, who had supported the linemen’s strike the year before.

The original caption from the Examiner of May 8, 1907 says the photograph shows the arrest of lineman John Riley, “who obstructed the cars and fought the police until he was beaten into insensibility…” Examiner/SFHC/SFPL/SB 18

A mounted policeman quirted the linemen’s horse to drive it from the tracks, and then began whipping the linemen, who fought back with wrenches. Other police swarmed onto the wagon and clubbed lineman John Riley until his “scalp was laid open to the bone,” according to the Los Angeles Times. Riley and lineman William Hannan, who was also beaten, were arraigned on various charges. They had not laid a hand on the Farley scabs, but they had challenged the power of Patrick Calhoun, the president of United Railroads.

Weeks later, IBEW Local 151 officially joined the Street Carmen strike. Calhoun was facing indictment by a grand jury on bribery charges (as were executives at two other IBEW 151 employers: PT&T and PG&E). But ultimately Calhoun had the resources to simply outwait the strikers. The strike collapsed in the fall. Its human toll included 31 killed and some 1150 injured.