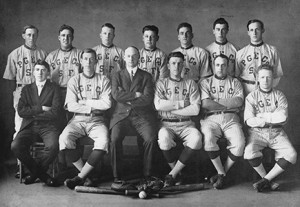

Utilities used “employee associations” in the 1920s and 1930s to divert interest from union organizing. PG&E’s employee association sponsored the baseball team shown here. Pacific Gas & Electric

L. L. “Mitch” Mitchell was 15 when he went to work as a “whistle punk” for the Sugar Pine Lumber Company near Fresno in 1931. Mitchell’s job was to tote limbs to stoke the fire of a big steam engine. The men he worked with belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

“That’s where I really learned what union power was,” Mitchell recalled.

“Their way of getting things was job action. You asked for something. If you didn’t get it, you quit work. It was just that simple. If the grub was no good, you don’t work the next day. If the beds are no good, you don’t work the next day. You know, just until you get new beds.”

The IWW believed contracts tied you down. They wanted the freedom to take action whenever they wanted something changed. For Mitchell, this attitude toward work was a revelation:

“Their own strength was the thing. You can one guy, the whole job walks off. They were united.”

In 1935 Mitchell was offered a job at PG&E. Officially, he was a grunt on a line crew. But he believed he got the job because he could play baseball. PG&E’s company union needed an infielder for its team. It was the same company union that PG&E had used to snooker its employees into abandoning the IBEW in 1921. Now they’d hired a shortstop who’d cut his eye-teeth in the industrial unionism of the IWW.