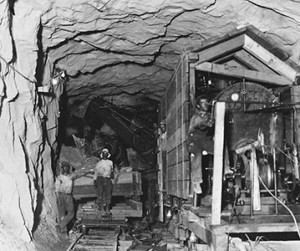

Workers build a tunnel for the Kerckhoff Powerhouse project in 1920. Working for a California utility back then meant you had no say in your wages or safety. IBEW 1245 Archive

The “Roaring Twenties” were grand times for industrial magnates and Wall Street speculators, but not so much for American workers. Union membership declined as real unions were replaced by toothless company unions—at PG&E and elsewhere. The richest 1% of Americans captured 70% of the nation’s income growth, vastly widening the gap between workers and the wealthy.

Three events in 1935 gave utility workers a chance to get their unions back.

The first was utility regulation. Utilities were dominated by vast holding companies that ripped off consumers and investors alike. President Franklin Roosevelt persuaded Congress to pass the Public Utilities Holding Company Act to cut utilities down to size.

Second, Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act, which for the first time gave workers a legal right to choose a union by majority vote at their workplace.

Third, John Lewis, president of the Mineworkers union, broke away from the stodgy American Federation of Labor (AFL) and formed the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CIO provided a model for PG&E workers who wanted to organize a single industrial union at the utility.

In 1937, the AFL and the CIO were competing to organize PG&E workers. Labor was now a house divided. Local 151, in its last dispatch to the IBEW Electrical Worker, summed up the workers’ dilemma:

“We are trying to organize the electrical men in our privately owned utilities and we have a hard nut to crack. The men do not know which to go into, whether the I.B.E.W. or the C.I.O.”