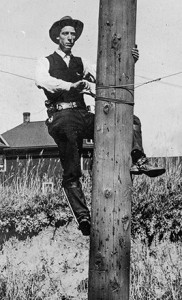

William S. Junkin working as a lineman in Oregon in the early 1900s, prior to leading the 1913 strike at PG&E. Oregon Historical Society

The PG&E strike of 1913, an exuberant and calamitous spectacle lasting eight months, was described by historian Charles Marsh as “greater than almost any other strike in the history of the industry.” The strike was an attempt by the IBEW’s Pacific District Council to flex its muscle at PG&E by uniting the major crafts at the utility in the newly-formed Light and Power Council of California.

Heading this new multi-craft Council was William S. Junkin, a Portland lineman. In addition to the IBEW, the new Council included Gas Workers, Boilermakers, Machinists, and Stationary Firemen. PG&E General Manager John Britton resisted their wage demands and proposed arbitration, but the Council decided to test its power and declared a strike on May 7, 1913. From Butte County in the north to Fresno in the south, about 1700 workers walked off the job.

From the first day, the strike interrupted service on several electric railway systems, at least for short periods. Britton immediately recruited university students as scabs to run power plants. Britton told San Francisco Mayor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph that strikers posed a “serious danger” to PG&E property and demanded police protection.

Sunny Jim was director of the Chamber of Commerce but enjoyed a reputation as “mayor of all the people.” He owned a popular house of prostitution called the Pleasure Palace and had been elected mayor the previous year with strong support from union members. Sunny Jim passed on Britton’s request for protection to the chief of police, but declined to recommend that police get involved.

But soon enough the strike would engulf the company, the union, general commerce, and the wider labor movement.