I came to Local 1245 in 1981 with one job on my resume – I had worked for Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers.

I first worked for the UFW in the summer of 1968. I was 16 when I got to the Union’s headquarters in Delano after driving across the country from my home outside Philadelphia. I spent that summer working for the UFW newspaper, El Malcriado, and operating the union’s Gestetner offset press. In the summers of 1970 and 1971 I worked as an organizer in the UFW boycott office in Philadelphia.

From 1972 until 1980 I worked for the UFW legal department in California, first as a legal worker and then, after passing the Bar examination in 1976, as an attorney. I worked as legal support for strikes and organizing drives in small farm towns from the Imperial Valley north through the Coachella Valley, the San Joaquin Valley, and the Salinas Valley.

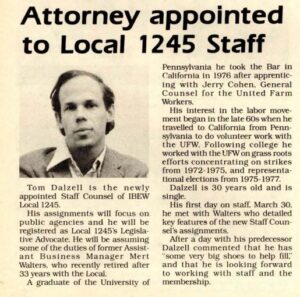

Dalzell’s hiring announcement from a 1981 edition of the IBEW 1245 union newspaper

When Jack McNally hired me as the Local 1245 staff attorney in 1981, he told me that he had done consulting work for the UFW pension plan in the late 1970s and he knew that the UFW lawyers were fierce and effective bad asses.

As a lawyer for Local 1245 for 25 years and as business manager for 15 years, my work has been informed and guided by lessons that I learned in my time with the UFW, and by those with whom I worked and from whom I learned – Cesar Chavez, Gilbert Padilla, Marshall Ganz, Dolores Huerta, the late Jessica Govea, Jerry Cohen, Sandy Nathan, and others.

On the face of things, it is not obvious that lessons learned with the United Farm Workers could be translated to working with Local 1245 and its members. Many farm workers in California are immigrants, and their work would be considered by labor economists to be low-skill, low-wage jobs with no history of union representation. The structure and character of the United Farm Workers drew on the civil rights movement and the leadership of Dr. King, the Cursillo apostolic movement of the Roman Catholic church, Danilo Dolci’s non-violent movement against squalid rural poverty and the Mafia in Sicily, Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement, Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent independence movement against British rule, and, in a cultural sense, the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th century. There was a strong ethos of sacrifice, epitomized by Cesar’s water-only public fasts and a volunteer staff structure. The employers we dealt with were passionately anti-union first- and second-generation immigrants from Armenia, Italy, and the Slavic nations of central and eastern Europe. Negotiations were not nuanced; they were exercises in brute strength. As a general matter, the UFW was known for public displays of worker power but not for being good at the details of contract administration. Strikes were common.

On the other hand, Local 1245’s members are high-skill, high-wage workers. We don’t draw on the culture of other movements, and our structure is traditional, that of the American labor movement. We do not have an articulated ethos of sacrifice, although many members of our staff take a significant reduction in pay when they come to work for the local. We have rarely seen the virulent anti-union animus that we saw in the UFW, although Michael Yakira’s tenure as CEO at NV Energy and the city councils of Gridley in the late 1970s and Redding ten years ago could have played in the minor leagues of grower anti-union animus. We have always been good at contract administration and our negotiations are often nuanced. Strikes are rare.

The contrast between the two workforces and the two organizations is obvious. Even so, what I learned working with the United Farm Workers served me well with Local 1245.

Workers Exercising Control Over Their Lives

A central premise of the UFW was that the most important purpose of a union was to give workers some control over their lives. Without a union, the only control that a worker has over their working life is to quit. Union members can — and do — exert control by acting collectively, and they achieve far more than they could individually. I have lived every day with Local 1245 holding that belief always close.

Nothing rewards me more than to see our members step up and join the collective effort to control their working lives. I think of Danny Mayo inviting a PG&E vice president to take a ride with him to see the true state of the grid. I think of Lloyd Cargo, for one, launching himself from the life of a PG&E Gas Service Representative to the life of a Local 1245 Business Representative, and then an Assistant Business Manager with responsibility for the PG&E grievance procedure. I see the fire in the eyes of Organizing Stewards like Melissa Echeverria and Kevin Krummes, doing things that they never dreamed they would do.

You can’t calculate the value of dignity using a slide rule or calculator, but it comes from stepping up to exercise control – and it’s worth a lot. Just look at Jaime Tinoco and what he has accomplished for his fellow members at the City of Lompoc – stepping away from the Teamsters, being on their own for a year, and then playing the long-game with the City, resulting this year in tremendous wage improvements because of our political activities with the City Council. To Danny, Lloyd, Melissa, Kevin, Jaime and hundreds of others — Cesar is looking down at you and smiling.

Leveraging Outside Pressure

When I was with the UFW, we understood that our opponent, California’s agriculture industry, was more powerful than we were, and we knew we could not win a war against the industry on our own. The growers’ control was just too pervasive, so we had to take our fight beyond the San Joaquin Valley to have any chance of victory.

We looked to the civil rights movement, which faced a similar problem in the South. The battle for equality and justice would never be won if it were only in the South. Segregationists controlled every institution within the power structure of the South, and no number of lunch counter sit-ins or marches could dislodge those who held the reins of racism. Dr. King and other leaders of the struggle in the South came up with the plan of seeking support in the North for the fight in the South. Only by leveraging power from outside would there be a chance of victory in the South.

The UFW application of this principle was the grape boycott. The strike itself, even with the accompanying publicity in California, wasn’t enough to get growers to recognize the union and negotiate contracts. But pressure in the market, through declining grape sales, could force their hand. Five years after the grape strike began in Delano, the UFW had grape boycott offices in dozens of cities in the United States, Canada, and Europe. By appealing to the public beyond the San Joaquin Valley, the UFW built the pressure needed to force grape growers to recognize the union and sign contracts.

We have used this principle many times within Local 1245. We went to the public when PG&E was threatening massive layoffs in the 1990s, with Jack McNally leading a demonstration against PG&E on the steps of the California Public Utilities Commission in the rain. We went to the public again when PG&E was threatening to cut clerical wages. But the most potent example of how we have leveraged outside pressure to resolve a fight that we couldn’t win in traditional means was with Nevada Energy ten years ago.

At the time, Michael Yakira was the CEO, and without warning in negotiations, he made clear the Company’s intention to drastically reduce retiree medical benefits for workers who had given their entire careers to the company with an expectation of retiree medical.

Retirees became the core of resistance. We went to faith groups. We went to other retiree groups. We went anywhere we could find support for NV Energy’s workers and retirees. The Labor Movement, especially D. Taylor of UNITE HERE Culinary Local 226 in Las Vegas, really stepped up for our retirees.

When a company vice president went to New York to accept an industry award, we worked with NY unions, including IBEW Local 3, UNITE HERE Local 100, and Peter Ward of the Hotel Trades Council, to turn out hundreds of picketers at the event. The industry group giving NV Energy the award called the police. None showed up. Why not? Our friends in labor met with the police department and made sure that the department didn’t badger our picket line. In fact, the police union’s chaplain came to the picket line and offered a blessing for NV Energy’s retirees.

It all added up – we were able to negotiate an agreement that made retirees whole for their retiree medical losses and reinstated the discontinued benefits.

There you have it – from the civil rights movement, to the UFW, to Local 1245, leveraging outside pressure is a tactic that’s tried and true.

Work Ethic

In the UFW, we worked hard, which runs counter to the image of the 1960s and a youthful shunning of hard work. If you had an office job in the Union, the expectation was ten hours a day Monday through Friday and nine hours on Saturday.

On strikes and organizing drives and the boycott, our hours were not fixed, but they were longer. Getting up at 3:00 in the morning to meet picket lines as they headed out to the fields became second nature to me.

This type of work ethic is drilled into Local 1245 business reps and the administrative staff. They may not have regular hours, but their day starts early, ends late, and after the pandemic their job will again involve a lot — and I mean a LOT — of driving. If we find that we have hired someone who didn’t understand the demands and doesn’t live up to our expectations of working hard, we politely give them a chance to pick up their game. If that doesn’t work, we let them go. We know how hard our members are working, especially in fire season or otherwise when a sustained rebuild effort is required. As their representatives, we owe them a strong work ethic – work hard, or don’t work here.

Five Smooth Stones

Our opponents — be they signatory employers, non-signatories trying to do work without a contract, or non-utility entities trying to take our work — are inevitably richer and more powerful than we are. How do you fight somebody who is bigger and stronger and more powerful than you?

We were faced with that issue in the UFW. When the grape strike began in Delano, Cesar lured Bakersfield-born Marshall Ganz from the Southern Non-Violent Coordinating Committee to work with the farm workers. Marshall had worked in the civil rights movement in McComb, Mississippi, and he was a natural fit with Cesar’s theories of asymmetrical conflict.

Marshall became one of the brightest organizers on Cesar’s staff. In laying out a campaign against a bigger and more powerful opponent, Marshall would remind us of the story of David and Goliath, found in the Book of I Samuel, Chapter 17. Before going into battle against Goliath, David chose “five smooth stones” out of a brook and then went into battle with the smooth stones which would fly true, as well as the God of the armies of Israel.

You know how that story ended – the small David killed the bigger, stronger, more powerful Goliath. He stunned the giant with his first stone, and then used Goliath’s own sword to cut off his head.

The lesson for us in the UFW and for us in the IBEW is simple – choose the stones with which you are going to fight carefully. They can make the difference.

How is it possible that, in 2018, we were able to defeat Nevada’s Question 3, which would have deregulated the electric utility industry to the great disadvantage of our members? We were facing a super-funded campaign bankrolled by the gaming and technology industries, which had won a decisive victory the first time the measure was on the ballot two years earlier. How could we win?

We went to the brook and chose five smooth stones. We worked with the faith community throughout the state. We worked with minority groups whose constituents stood to lose significant benefits offered by a regulated utility. We worked with a Nevada labor coalition. We worked with rural Republicans for whom a high-quality utility service was only possible in their districts with a regulated utility. We worked with NV Energy. And we worked with ten other IBEW Locals that we had helped over the years, including the coalition of IBEW Locals with members at other Berkshire Hathaway-owned utilities. They each sent five members to Las Vegas for a week of precinct walking. We chose our stones well. We won, and we won big.

Another parable – how did we emerge from PG&E’s second bankruptcy in 20 years with a five-year contract, no layoffs, no reductions in benefits, and wage increases well above the utility industry market? During the bankruptcy, we had our smooth stones:

- A strong relationship with Governor Newsom and his office (especially Ann Patterson and Angie Wei), thanks to 20 years of building on ties initiated by Local 1245’s Hunter Stern when Mayor Willie Brown appointed Newsom to the City’s Parking and Traffic Commission back in 1996;

- A strong relationship with leaders in both parties of the legislature, thanks to our lobbyist Scott Wetch and Bob Dean’s outreach to GOP legislators, as well as Democrats, over the years;

- Local 1245 staffer Doug Girouard’s hard and brilliant work on the official unsecured creditors’ committee;

- The ability of our staff organizers, Rene Cruz Martinez, Eileen Purcell and Fred Ross Jr., to mobilize more than 100 organizing stewards on very short notice to lobby the legislature on our behalf;

- Eric Jaye and his squad of political consultants from Storefront Political Media in San Francisco;

- Our regulatory lawyers Marc Joseph and Rachel Koss from Adams, Broadwell and Joseph;

- Good bankruptcy lawyers (Locke Lorde from New Orleans) working with our in-house attorney Alex Pacheco, and an Executive Board that saw their importance;

- A willingness to work with all groups involved in the bankruptcy, including bondholders who did not support PG&E’s plan for reorganization, most notably Jeff Rosenbaum of Elliott Management;

- And in the end, a willingness to work with PG&E CEO Bill Johnson and equity holders led by Tom Wagner of Knighthead Capital to get the plan confirmed in bankruptcy court.

It was a complicated play that had us in an adversarial relationship with PG&E’s Board of Directors, but it worked, and it paid off.

I have told our shop stewards the story of David and the five smooth stones. Steve Mayfield is a steward in the Materials Department who has heard the story several times. He gave me a shepherd’s sling made in the style that David would have used, and a bag of five smooth stones. Good gift! I’m taking it with me, but leaving the lesson with you.

Listen to the People Around You

This one is a tougher lesson. In the early years of the UFW, Cesar had a trusted circle of staff around him. When he had an idea, they debated the idea. When they had an idea, they debated it. By this process, Cesar culled out the bad ideas, the impractical ideas, and the ideas that didn’t survive a risk-benefit analysis. He encouraged the staff to bring ideas to him — even outside-the-box, counter-intuitive, and ridiculous ideas.

Starting in the mid 1970s, Cesar listened less and less to the trusted circle of staff around him, and the circle got smaller and more inclined to agree with anything he said. This was the first stage of failure, and complete failure in fact came shortly thereafter.

As Business Manager, I was determined not to make that mistake. I had smart and talented people to work with – the late Bob Choate, the late Howard Stiefer, Sam Tamimi, Ron Cochran, Bob Dean, Joe Osterlund, Dorothy Fortier, Ray Thomas, Bryan Carroll, Jenny Marston, and others. I often consulted Jack McNally and Perry Zimmerman, my predecessors. There wasn’t an idea that we didn’t debate. We didn’t always agree, but we formed consensus.

I can’t think of a big mistake that we made, and I owe that to everyone’s willingness to think about every idea and debate it. I can only think of two decisions that I made over the objection of my closest advisors. As luck would have it, I was right about one and wrong about the other. Our rule was that we were many voices behind the meeting room door, but when we walked out of the meeting we spoke with a single voice. It worked.

Collaboration with Employers

The relationship between the UFW and growers under contract strongly resembled the relationships that exist in open class warfare – we hated them, and they hated us. But as the union matured, there were exceptions.

In the late 1970s, the UFW members in the lettuce industry took a bold step towards collaboration. Lettuce cutters were the elite in farm labor – very tightly knit, hard-working, piece-rate workers who made a lot of money relative to most other farm workers. They were to farm work as linemen are to electric utility work.

In early 1979, we struck lettuce growers who had refused to renegotiate their contracts. It was a rough strike. One striker, Rufino Contreras, was shot and killed by growers in the Imperial Valley. We came out of that strike with only a few lettuce contracts, and because our wage rates were higher than the non-union, our signatory growers were having a hard time competing with the lower-paying competition.

To address this issue, Marshall Ganz turned to the lessons learned by Harry Bridges and the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen Union when containerization of ship cargo threatened the loss of many longshoremen’s jobs. Bridges negotiated a labor agreement to compensate longshoremen for lost jobs and wages resulting from containerization and other mechanized cargo-handling techniques. Bridges, a labor leader who was often accused of being a communist, also agreed to work with his members to improve productivity whenever possible.

Back to the lettuce fields – Ganz and a committee of lechuguero (lettuce cutter) shop stewards from the largest signatory lettuce company developed a quality program. If that company’s lettuce was more neatly trimmed and packed than the competition’s, the company would have a leg up on the competition. Similarly, if the competition decided that it was too muddy to cut, our signatory company could make a killing if our crews would agree to work in sloppy, muddy conditions. They would not work in the mud normally, but as part of this program, they were willing to.

The lesson I took away from this is that collaboration is okay, sometimes. If the most militant union of the 1970s could bring itself to collaborate with growers in an industry that sometimes seemed feudal, so can we at 1245. We must be clear about why we are doing it, have a clear understanding of what our role will be, and know under what circumstances we will end our collaboration. But collaboration should not be automatically off the table.

I will give one example of how collaboration has paid off for us. In May of 2013, we learned that Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway had acquired Nevada Energy. We were concerned, because we had heard disturbing stories of aggressive bargaining by Berkshire at other utilities it owned. In the months before the takeover, we commissioned a forensic audit of Berkshire Hathaway. That audit supported our assumption – Buffet and Berkshire were too big, too strong, and too clean for us to think that a frontal assault could work.

Instead, with the guidance of political consultant Mary Hughes, we formed a coalition of the IBEW locals that represented Berkshire utilities in Illinois, Iowa, Utah, Washington, and Oregon. Working with several IBEW vice presidents, including Lonnie Stephenson (who is now the IBEW International President), we agreed to propose collaboration to Berkshire. They jumped on our idea, and the tone of contract negotiations immediately took a 180-degree turn. No more take-away proposals, and no more concessions. Chalk one more up for collaboration.

Use the Law

At the peak, we had 18 lawyers working for the UFW out of offices in the Glikbarg Building on West Gabilan Street near the Greyhound Station in downtown Salinas. In the early years, most of the work we did was defensive – fighting injunctions against strikes and defending strikers who had been arrested. As we got better at what we were doing, we devised ways to make the law work for us. In 1975, the State of California enacted the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which, like the National Labor Relations Act had done 40 years earlier for other workers, created a legal framework under which farm workers could organize into unions that growers had to recognize and bargain with.

The Western Conference of Teamsters was also organizing farm workers, and because they were led by white men who did not militantly advocate for farm worker members of color, the growers strongly preferred the Teamsters over us. We launched a massive organizing drive in every agricultural valley in California. Embedded in each organizing team was a legal team – a lead lawyer (until a few of us non-lawyers showed that we could lead a legal team) and a group of legal workers. Bob Purcell, an organizer with the UFW who went on to a stellar career with the Laborers International Union of North America, coined our motto of, “Organize to win and document to defend the victory.” The legal teams documented by declaration every act of favoritism for the Teamsters and every coercive threat to our members that the growers made to discourage support for the UFW.

Looking back, what we did was amazing. Using our 30 legal workers and 10 of our lawyers in organizing drive after organizing drive, we provided legal cover for our organizers and we were ready to defend grower challenges to election results. We had a good law, and we used it.

A year before the farm labor law was enacted, we filed an anti-trust suit against the lettuce industry as well as the Western Conference of Teamsters, centered around sweetheart contracts the Teamsters signed with the industry in 1970. The late Bill Carder had the original idea for the suit and drafted the complaint that we filed in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California. The late John Rice-Trujillo was the lawyer who coordinated the massive work that the suit generated. It created pressure on the Teamsters, who, in early 1977, signed a jurisdictional agreement to leave organizing in the fields to the UFW. Four of our lawyers negotiated the jurisdictional pact – Jerry Cohen, Sandy Nathan, George Lazar, and Kirsten Zerger. This left the UFW as the only union organizing farm workers, and we were operating under a pro-union labor law administered by a pro-worker board. What could possibly go wrong?

That is a tease, because the answer, which we didn’t know at the time, was that when given an open road with a breeze to our back, what went wrong was everything. Given the chance for an astonishing victory that we had been dreaming of for 17 years, we self-destructed. But that’s another story.

In Local 1245, we followed the lesson of using the law as an offensive weapon several times. Ray Thomas, who led the public/private sector group within 1245 along with Dennis Seyfer until recently, was our best tactician in this arena. When the City Council at the City of Redding stripped retiree medical from other bargaining units, Ray asked for authority to sue the City. I agreed, and our lawyers won in Superior Court and won in the Court of Appeal. Through litigation, we held onto an important benefit that most City employees lost.

In public sector negotiations, Ray Thomas understood that the legal prohibition on bleeding enterprise funds into a City’s general fund was a lever. In several public sector negotiations, Ray asked me to authorize the use of forensic accountants to determine if a city was illegally using enterprise funds to subsidize its general fund. It worked like a charm. Ray knew the law inside and out and he had accounting proof of violations of the law. Instead of litigating the issue, Ray had the ability to identify the lack of compliance and suggest corrective action that benefitted our members and avoided litigation. And got us a contract.

In the mid 1990’s, I filed lawsuits on behalf of our ditch tender members working at irrigation districts, seeking overtime pay that the districts had refused to pay. I filed suits in federal district court against the South San Joaquin Irrigation District, the Merced Irrigation District, the Modesto Irrigation District, and the Oakdale Irrigation District. At different stages of ligation, we settled all four cases with hundreds of thousands of dollars of payouts for our members.

Lastly, in April 2007, the California Supreme Court issued a decision holding payments mandated by California Labor Code § 226.7 for meal and rest period violations are “wages” and not “penalties.” The Court’s ruling that these payments constitute “wages” made claims brought under section 226.7 subject to a three-year statute of limitations rather than a one-year limitations period for “penalties.” We prepared litigation against several employers, most notably PG&E. Because of our long collective bargaining relationship, we agreed with the Company on an administrative procedure to resolve claims. Bob Dean and Joe Osterlund, who were both Business Representatives at the time, took over and took off. By the time they were finished, PG&E had paid our members $40 million dollars for missed meals over a three-year period.

The law is not a defense in and of itself, and it is not a substitute for union representation. It is, though, an arrow in a union’s quiver.

Stewards and Arbitrations

I don’t remember what I told Jack McNally about my arbitration experience when he interviewed me for the job, but it probably wasn’t the whole truth. I had done exactly one arbitration with the UFW. I did 300 arbitrations for Local 1245, but I did them as I would have done an arbitration with the UFW. I knew that the knowledge of our shop stewards and members was the key to success.

The first arbitration that came up was with Sonic Cable in San Luis Obispo. I began my preparation for the case by meeting our lead steward Scott Lawson and several other stewards at a pie shop in Paso Robles. I remember the pie, and I remember Scott and the stewards telling me about the background of the grievance. I ran out of yellow pad paper and finished my notes on napkins. I organized what they had told me and called the lawyer for the company. I laid out our case and asked him to explore settling the case. We settled the case with the remedy granted in full.

The next case I had (and this was 40 years ago, but I remember it well) was with SMUD, and it involved overtime pay for after-work training. I showed the case to Corb Wheeler, one of our PG&E fact finders, and he saw an avenue that I hadn’t seen. I then met with Hank Lucas, our rep at SMUD, and a group of SMUD stewards. I ran Corb’s theory past them and – bingo – they piled on with stories that backed Corb’s theory. I presented the case. We won. Remedy granted in full.

One last story to illustrate this point came out of negotiations with Citizens’ Utility, the company which is now Frontier. The company failed to implement a negotiated wage schedule, relying on language that was not in the contract. I had the entire negotiating committee off work for a few days to prepare for arbitration. I gathered all their thoughts and documents, and we went into arbitration before Arbitrator Barbara Chvany, a bright, thorough, and fair arbitrator who I knew well. The company’s lawyer was from New York, and he devoted his entire opening statement to a harsh scolding of Local 1245; how could we even think of filing this grievance, let alone taking it to arbitration, when we had to know that we had no chance of prevailing?

You probably have guessed it, but we won. Remedy granted in full. It was the biggest arbitration payout in my career. I relied on our committee. The employer attorney would have benefitted from reading Proverbs 16:18 before making his opening statement – “Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before the fall.”

Organizing Stewards

This brings me to the organizing stewards. The UFW could always mobilize farm workers for demonstrations at the Capitol, in support of a boycott, for a march, or in the fields. This was mobilization, not organizing, but it was an effective tool. Beyond that, we had cadres of organized farm workers who were willing to pack up and go to cities around the country to work on boycotts. In 1967, and again in 1973, several hundred workers, many of whom did not speak English, went to cities around the country to build boycott operations. Without the boycott, we would not have won contracts in the grape industry, and we would not have won passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

From 1981 until 2009, I saw nothing that would make me think that Local 1245 would ever need to mobilize or organize its members as we had in the UFW. In 2009, I was rudely disabused of that opinion. Local 1245 faced a problem that we had not faced in the past and that we were not prepared to fight – a strong anti-union attack by a major signatory employer. The CEO of Nevada Energy, Michael Yakira, was openly anti-union and anti-worker. He launched an unprecedented attack on retirees and their medical coverage. Our historical civil, business relationship with Nevada Energy was out the window and our historical ways of resolving disagreements would not work.

The solution came from our members and our retirees – organize and mobilize. From the UFW, I knew that if we asked, our members and retirees would answer, and they would grow in the process. So we reached out to retirees and active members and, in real time, built a fighting organization. We had rallies. We had picket lines in front of company headquarters for the first time in our 60-year collective bargaining history with the company. We made a compelling video featuring retiree Sylvester Kelley, and we put retiree Ron Borst with his made-for-radio voice on the radio. As I mentioned above, we had a massive picket line in New York when the company’s CFO accepted an award at a dinner there. We won the fight for retiree medical coverage, but more than that, it was the impetus for what would eventually become our organizing steward program.

Just as we created safety stewards to help keep our members safe, we created organizing stewards who are trained in organizing and campaign work. They come from all walks of life and lines of business, they are multi-generational and as diverse as could be, but they all love a good fight. Over the years, they’ve worked on hundreds of campaigns, including union organizing drives as well as elections for worker-friendly candidates and ballot measures. Through these unique experiences, our organizing stewards begin to see themselves as change agents who can be part of making history and are forever empowered by the transformative impact that comes from becoming active and engaged leaders and organizers.

In the process, we have also built power — in Sacramento, within the IBEW, and within the labor movement — that is disproportionate to our size. We won our campaign to defeat Question 3 in Nevada because of the power of the organizing stewards. We won legislative victories in Sacramento in 2019 because of the power of the organizing stewards. And we did so well emerging from PG&E’s bankruptcy because of the power of the organizing stewards.

Conclusion

I am not saying that everything I have done at 1245 is based on what I learned in the UFW. Every day at 1245, I have learned from our members and staff. I learned from the Business Rep Joe Valentino when he faced down a decertification movement at Alameda. I perfected good cop / bad cop tactics from Business Rep Jim Lynne in negotiations with PGT. I learned from Debbie Mazzanti when she played crazy with unfriendly supervisors and reverted to funny and reasonable with less hostile supervisors. I learned from shop steward Larry Giovannoni about the benefits of having a clerk from the finance department in City of Healdsburg negotiations. From Mike Connell, I learned about the importance of understanding office politics and relationships in negotiations with the Truckee-Donner Public Utility District. I learned how much of an asset good costing is from Stu Neblett and Mark Newman and Ron Moon and other spreadsheet jedi on PG&E negotiating committees. And so on.

What I learned with the UFW was a brand of unionism and organizing that had been handed down from John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers to Saul Alinsky of the Industrial Areas Foundation to Fred Ross of the Community Service Organization to Cesar Chavez.

The torch that I carried is now passed on. I am sure that Bob Dean and the staff and stewards and organizing stewards will add to our play book. I have declared my complete allegiance to Bob with all my heart. I can’t wait to see what he, and all of you, will accomplish.

Tom Dalzell is a 40-year member of IBEW 1245. He served as Business Manager from 2006-2020.