Part of Bobo’s lineman memorabilia collection

In 1956, when Vicente “Bobo” Piuela was nine years old, he had his first exposure to utility linework. He was out on a walk with his mother, Lolita, in Watsonville when he walked right into a down guy wire. “Watch where you are going,” his mom told him, but Bobo’s mind was focused on the wires, and the men who were working on them. He was initially mad at the pole, and yet completely fascinated by what it was holding up. He started to wonder about the wires and how they worked. Were they telephone lines, or electric? And what about the insulators? What are they? He tried to ask the linemen, who quickly warned young Bobo not to touch them, as they’re intended to protect him from electric shock.

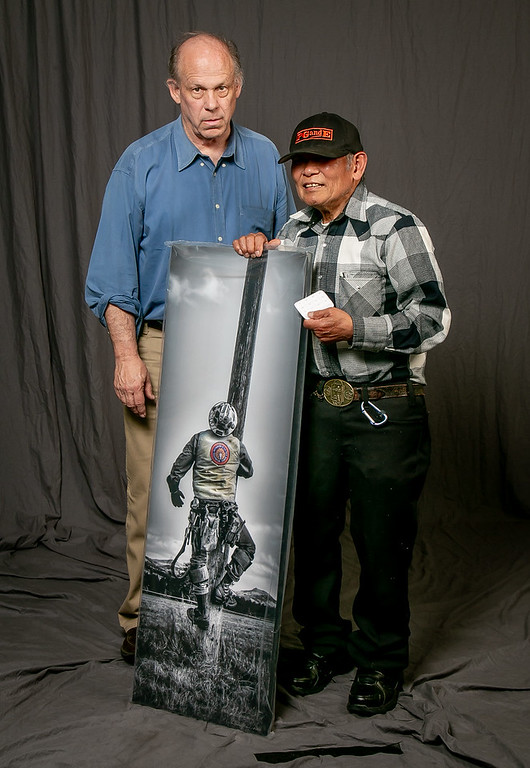

Bobo, with his collection, in 2019.

Bobo’s interest in linework quickly transformed into a passion. His dream was to one day become a lineman himself. But unfortunately, that would never happen — because Bobo was deaf from childhood, and as his friend Lanny Martin once explained to him, linework is just too dangerous for a deaf person, because he wouldn’t be able to hear a warning if there was a problem.

But that didn’t put a damper on Bobo’s passion. He was an avid learner and collector, and when a schoolmate’s dad, who worked for the telephone company in Monterey, brought Bobo some stuff from work, he was absolutely ecstatic.

In 1959, after spending some time at a small deaf school in Watsonville, Bobo enrolled in the California School for the Deaf, which at that time was in Berkeley. While living in Berkeley, he taught himself how to climb, first by practicing on trees, and then on utility poles – even swapping out secondary insulators at night. No one noticed.

He began taking telephones apart so he could figure out to put them back together. His friend’s dad would explain some of the aspects of how the equipment worked, and the more Bobo learned, the more he wanted to learn. He voraciously studied every book and manual that he could get his hands on. The specific terminology was hard for him, but he quickly learned how to identify the marks on the poles — “high voltage” meant danger, “electric” meant don’t touch, “telephone” was no danger. He even tested some low voltage shocks on himself with a telephone, just to see what electricity felt like.

Bobo shows off his first model line truck, which he hand crafted as a young boy.

Around that time, Bobo also began making models of PG&E line trucks. He was just 13 when he built his first model truck – self-taught, of course, as was his modus operandi. He used a photo for reference and scale, and would proceed with trial and error until he got it exactly right. He was told that his models are so accurate that they could be used in the classroom as teaching tools.

In 1967, he graduated from the school for the deaf and returned to his home on the Central Coast. There, he spent hours just watching the linemen in his community as they worked. They often had to tell him to step back, which he did… but would inch closer again, always trying to get a better look.

He recalls a time when he got to see a transformer change-out on 7th St. in his town of San Juan Bautista. The equipment was heavy, and it was hard, slow job. But what struck Bobo was the way the crew would use hot sticks — and the moment when he saw the sparks.

He followed the crew from job to job, learning the difference between 4kv, 12kv and 21kv. The linemen grew fond of young Bobo, and as a token of affection, they’d often give him old insulators. At that time, they were doing a lot of undergrounding – and as a result, Bobo would get a lot of insulators. Those insulators, along with his models, his books, and the items he got from the phone company, were the start of his one-of-a-kind utility memorabilia collection. That collection would continue to grow for the next 50-plus years, gradually transforming his home into something that more closely resembled a museum.

He followed the crew from job to job, learning the difference between 4kv, 12kv and 21kv. The linemen grew fond of young Bobo, and as a token of affection, they’d often give him old insulators. At that time, they were doing a lot of undergrounding – and as a result, Bobo would get a lot of insulators. Those insulators, along with his models, his books, and the items he got from the phone company, were the start of his one-of-a-kind utility memorabilia collection. That collection would continue to grow for the next 50-plus years, gradually transforming his home into something that more closely resembled a museum.

Bobo’s substation model

When he was in his early 20s, Bobo constructed his most outstanding model — a full mock-up of a nearby substation, complete with switches that work mechanically. It was challenging for him, and he used a reference book to make sure the model was true-to-life. He was living with his father in Bakersfield at the time, and spent a full six months working on the model. Once it was finally complete, it was so enormous that he struggled to get it through the door of his house in San Juan! He showed it at a number of fairs, and even took a first-place prize at the San Benito County fair.

In his later years, he became a well-known face around insulator trade shows. He would earn money by recycling out-of-service parts, transforming them into works of art, and selling his unique wares. Between 1994 and 2016, Bobo sold 99 meter lamps and eight pole models with three-pot bank structure. He also made and sold 14 doll houses. He spent most of his earnings at shows and flea markets, where he picked up more and more items for his collection. Over the years, he’s collected about 400 insulators, mostly from Edison. He also has 344 meters, and a three-dial A Base.

Bobo showed Dalzell some of the reference books he’s collected and used to teach himself about linework

“It’s good to have a hobby. You don’t get in trouble,” he told me (via sign language interpreter) when I visited his home to view his collection in March of this year. I was struck by his positivity, his disarming grin, and his sheer genius – he truly knows more about utility work than most career linemen. And of course, I was blown away by his collection of memorabilia, the astonishing models he crafts by hand, his artwork, and the unique way that he has repurposed decommissioned utility equipment to give it new life.

Tom Dalzell presented Bobo with a certificate, artwork and IBEW 1245 membership card at the IBEW 1245 Monterey Pin Dinner on March 29.

Even though Bobo never got a chance to work in the utility industry, he’s cultivated so much knowledge and pride for the craft, and I wanted to do something special for him. So this spring, at the annual IBEW 1245 Service Awards in Monterey, I made Bobo an honorary member of IBEW 1245. I presented him with his very own union card, and an enlarged copy of a drawing of a lineman. This isn’t something I would do for just anyone — but Bobo isn’t just anyone. He’s a brilliant, remarkable mind, a highly skilled craftsman, and a kind-hearted individual who embodies all the traits we celebrate at IBEW 1245. He carries his union ticket around in his wallet and proudly shows it off to all of his lineman friends when he sees them around town.

I’m honored to call Bobo a brother. He’s an inspiration to us all.

–Tom Dalzell, IBEW 1245 Business Manager

I first met Bobo back in 1985 or 1986. At that time, I was a new foreman, and in accordance with General Orders 95 and 128, PG&E would send us out for compliance inspections along with a company auditor after new jobs were completed. On one of those inspections in Hollister, something caught my attention that would be the start of a wonderful friendship.

In the yard, there was a model of a utility pole inside a beautiful glass display case that struck me. The detail was incredible, and I could tell it was handmade. We had work to do, but the auditor told me he knew who made the model from his previous visits to the PG&E system, and assured me he would take me to meet him.

That night, we traveled to meet Bobo in nearby San Juan Bautista. When we got to his house, I felt like a kid in a candy store. I was blown away by all of the memorabilia he had collected. Bobo also had his creativity on display: he was making lamps out of old utility meters with hard hats for shades.

Some of the meters in Bobo’s collection

I told Bobo I could get him some more meters, and I started bringing him old equipment. At that time, we would take in meters as people were upgrading their systems. When my career started in San Francisco in the early 1970s, there was still old utility equipment all over the city from the 1920s, 30s and 40s. We were going to throw those old meters and tools away, so I would sign these things out and take them to Bobo by the bus load.

Bobo has been deaf since childhood. His mother, Lolita, told me that one day, while out for a ride with his dad, Bobo started making a big commotion in the back seat, which was unusual for him. He was fixated on something. Bobo’s dad looked out the window and saw workers going up a utility pole. He pulled the car over and learned it was a PG&E crew doing line work. He asked the foreman if he and Bobo could come back the next day to watch the crew work. They did, and Bobo brought his drawing easel. The pictures Bobo drew that day won a gold medal at the California State Fair.

Bobo and Lindsey bonded over a shared love of model trains and linework

Despite Bobo’s hearing impairment, communication has never been an issue between us. We had an instant connection over his utility memorabilia, and also over his love of old toy trains, an interest of mine as well. Our friendship blossomed from there.

Over the years, my wife and I would visit Bobo every two or three months and also enjoyed getting to know Lolita, who was heavily involved in the community. One of my most prized possessions is a gift from Bobo: one of his meter lamps with a hard hat shade.

–George Lindsey, 42-year IBEW 1245 member and PG&E Electric Crew Foreman

I met Bobo somewhere around late 2006 or early 2007. I was an apprentice lineman, renting a town house that came with a gardener as part of the rent. This was before PG&E issued uniforms, so I didn’t wear clothes that totally gave away that I was a PG&E guy. I had seen Bobo around the neighborhood, but didn’t get a chance to talk to him for the first month or two. Then one night, as I was returning home from work, Bobo was sitting on his truck tailgate waiting for me. He motioned for me to come over to the backyard, and pointed at my wooden pin cross arm horseshoe pits. He began to write down words on his note pad, and it was at that moment when I realized he was deaf. But I couldn’t believe what he was writing down — he knew everything there was to know about that cross arm! It was a wooden pin, single light cross arm that was made before 1960. This was the start of our friendship, and from that day forward, Bobo and I have been close friends, like family.

Skelton and Bobo share a fist-bump

During the next two years, we had many days writing back and forth on note pads. I remember one night when Bobo showed up late to mow the yard, and he looked through the window and saw my book of standards on the table. It was the large blue overhead book, and Bobo knew right away that I must be studying, because I didn’t come outside to meet him. He saw the pages that I was studying (it was the section on transformer connections, which I needed to learn for my upcoming wage progression test) and took off. I didn’t know what was about to happen, but out of nowhere Bobo showed back up with wooden pole models that he had built, complete with amazingly accurate transformers on them. They were perfect in size, shape, color, and even were wired correctly on both the high side and low side. I was blown away by his smarts, seeing as how he had never even taken lineman classes, had never worked as a lineman – yet somehow knew how to wire a transformer as if he’d spent years on the job. At that point, I realized just how special and rare Bobo is. For fun, I copied extra study guides from class and would give them to Bobo as “homework” – but really, he was the one teaching me. Bobo would finish the assignments so fast, and add so much detail — like voltage, delta or wye connections — in to the answers, that he was actually helping me understand transformers from a different angle.

One of Bobo’s model transformers

Because of Bobo’s deafness, no one would hire him to do such a dangerous job, but if given a chance, I know he could have done the job at a very high level. Bobo is a good climber – he told me that back in the day, he would climb up to secondary level and look around, and even change out insulators, swapping new ones for old ones that he liked or didn’t already have.

That brings me to his collection. Bobo not only has the knowledge and passion, he also has the obsession with the history of the trade, just like so many of us linemen. Whether it be books, models, or old insulators, Bobo collected them all. If you didn’t personally know Bobo’s history and were to sit down with him, you would leave the conversation thinking you were just talking with an old lineman.

–Ryan Skelton, IBEW 1245 Business Rep and former PG&E Journeyman Lineman

Photos by John Storey

Dalzell and Bobo at the Monterey Pin Dinner on March 29. Bobo proudly holds up him new union card.

Tom Dalzell presents Bobo with a certificate, artwork and IBEW 1245 membership card at the IBEW 1245 Monterey Pin Dinner on March 29.

Tom Dalzell presents Bobo with a certificate, artwork and IBEW 1245 membership card at the IBEW 1245 Monterey Pin Dinner on March 29.

Skelton and Bobo share a fist-bump

Bobo and Dalzell look through Bobo's extensive collection of linework reference manuals and books

Bobo and Dalzell look through Bobo's extensive collection of linework reference manuals and books

Bobo makes and sells lamps out of old meters and hard hats

Bobo shows off his first model line truck, which he hand crafted as a young boy.

Bobo shows off his first model line truck, which he hand crafted as a young boy.

Bobo repurposed this sign into a clock

One of Bobo's many models

One of Bobo's many models

Bobo's substation model

One of Bobo's models

Some of the meters in Bobo's collection

Bobo and Lindsey bonded over a shared love of toy trains and linework

Bobo, with his collection, in 2019.

Dalzell captures some photos of Bobo's models

Part of Bobo's lineman memorabilia collection